http://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/jan/07/when-cities-change-their-names-to-stupid-things-for-stupid-reasons

The strangest thing about Oregon, Ohio changing its name temporarily to Oregon, Ohio Buckeyes on the Bay, City of Duck Hunters? The fact that stuff like this is not uncommon

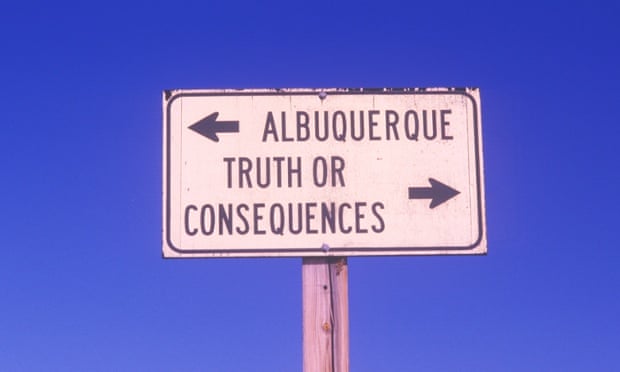

Truth or Consequences, New Mexico, renamed from Hot Springs in 1950 to win a radio contest. Photograph: Alamy

The strangest thing about Oregon, Ohio changing its name temporarily to Oregon, Ohio Buckeyes on the Bay, City of Duck Hunters? The fact that stuff like this is not uncommon

Truth or Consequences, New Mexico, renamed from Hot Springs in 1950 to win a radio contest. Photograph: Alamy

Would you like your birth certificate to state you were born in Google, Kansas? What about Dish, Texas? Joe, Montana? Or, perhaps: Oregon, Ohio Buckeyes on the Bay, City of Duck Hunters? That last one’s in Ohio, in case it wasn’t already obvious. And like the other two cities (and many more), Oregon, Ohio is undergoing a temporary name change – just until 12 January – when the Oregon Ducks (who are not from Ohio) will play the Ohio Buckeyes in the College Football Playoff National Championship.

It started when local Matt Squibb launched a petition asking the city council to “make a proclamation to change the name of the city for one day”. He explained: “I am not a huge Buckeye fan but I feel this game is important to a lot of people and I know many of those people are superstitious, so lets [sic] make this happen people!”

Nor is Oregon the only city in Ohio to take this step ahead of the weekend’s big game. Urbana, Ohio will also adopt a temporary moniker: in a nod to Buckeyes’ coach Urban Meyer, the town will drop an ‘a’ and simply be known as Urban, Ohioon the 12th.

Perhaps the strangest thing about all this is that it’s not uncommon. Changing a town’s name for a singular – even arbitrary – purpose, even if only temporarily, has a relatively long history.

Take Hot Springs, New Mexico, which in 1950 changed its name to Truth or Consequences to win a radio contest and have that popular radio game show broadcast from the tiny community once a year for the next half-century. They even named a park after the host, Ralph Edwards.

Google, Kansas (AKA Topeka) adopted its new name for a month, in an attempt to woo the web giant to establish superfast internet connections in random American cities through its Fibre for Communities scheme. And Clark, Texas renamed itself Dish, Texas in a deal with Dish Network in 2005. As part of the deal, the company hooked up 55 homes in the town with basic cable for free for a decade; in return, they got a bunch of free advertising (I’m giving them some right now).

Some names have been totally sold off. Half.com, a site that in 1999 was a successful online store (subsequently acquired by eBay in 2008, it still exists), paid Halfway, Oregon to change its name for a year to Half.com. And in 1989, actor Kim Basinger bought the town of Braselton, Georgia for $20m and renamed it after herself. (She eventually had to sell it off for $1m a few years later when she got into unrelated legal trouble.)

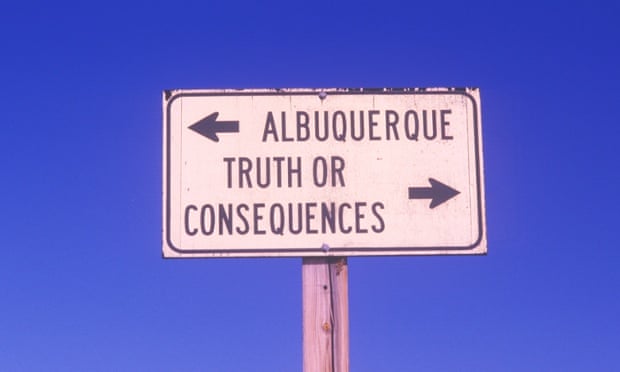

Halfway, Oregon, changed its name because of sponsorship from Half.com. Photograph: Alamy

It’s a strange thing, putting a price on a town. Each time, it reinforces the idea that a town isn’t merely a community, but a branding opportunity. Ask the people of Rocky Top, Tennessee. Last year, a major developer approached the fledgling Appalachian town, then called Lake City, and proposed to transform the city with a major new development. It would include an amusement and water park designed to attract tourists, along with hundreds of jobs and an estimated $50m in revenue, including $6m in taxes ... if the town changed its name to Rocky Top, a well-known bluegrass tune and the fight song for the University of Tennessee Volunteers. The idea was the name change could bring attention to a dying, former coal town. Lake City took the deal.

When CNN visited, they talked to Barry Thacker, head of the Coal Creek Watershed Foundation – so-called because before Lake City was Rocky Top, it was Coal Creek. The reason it was changed the first time, in 1936, was pretty much the same: there is no lake in Lake City, but “city leaders thought a name change would help draw tourists when the Tennessee Valley Authority put in a dam and a manmade lake several miles away.” Thacker disagreed with another renaming. “They did that once before … It didn’t bring tourists. Now, they’re doing it again,” he said. “You embrace your heritage. You don’t run away from it.”

Sounds about right. Except what happens when your town’s heritage is that it changes its name? Perhaps we’ll find out soon enough – maybe as soon as the next time the Oregon Ducks face the Buckeyes.

No comments:

Post a Comment